IMDB

This notebook was adopted from the Fast.ai github repository: https://github.com/fastai/course-v3 on 11/4/2019. Licensed under the Apache Version 2.0 https://github.com/fastai/course-v3/blob/master/LICENSE

%reload_ext autoreload

%autoreload 2

%matplotlib inline

from fastai.text import *

Preparing the data

First let’s download the dataset we are going to study. The dataset has been curated by Andrew Maas et al. and contains a total of 100,000 reviews on IMDB. 25,000 of them are labelled as positive and negative for training, another 25,000 are labelled for testing (in both cases they are highly polarized). The remaning 50,000 is an additional unlabelled data (but we will find a use for it nonetheless).

We’ll begin with a sample we’ve prepared for you, so that things run quickly before going over the full dataset.

path = untar_data(URLs.IMDB_SAMPLE)

path.ls()

It only contains one csv file, let’s have a look at it.

df = pd.read_csv(path/'texts.csv')

df.head()

df['text'][1]

It contains one line per review, with the label (‘negative’ or ‘positive’), the text and a flag to determine if it should be part of the validation set or the training set. If we ignore this flag, we can create a DataBunch containing this data in one line of code:

data_lm = TextDataBunch.from_csv(path, 'texts.csv')

By executing this line a process was launched that took a bit of time. Let’s dig a bit into it. Images could be fed (almost) directly into a model because they’re just a big array of pixel values that are floats between 0 and 1. A text is composed of words, and we can’t apply mathematical functions to them directly. We first have to convert them to numbers. This is done in two differents steps: tokenization and numericalization. A TextDataBunch does all of that behind the scenes for you.

Before we delve into the explanations, let’s take the time to save the things that were calculated.

data_lm.save()

Next time we launch this notebook, we can skip the cell above that took a bit of time (and that will take a lot more when you get to the full dataset) and load those results like this:

data = load_data(path)

Tokenization

The first step of processing we make the texts go through is to split the raw sentences into words, or more exactly tokens. The easiest way to do this would be to split the string on spaces, but we can be smarter:

- we need to take care of punctuation

- some words are contractions of two different words, like isn’t or don’t

- we may need to clean some parts of our texts, if there’s HTML code for instance

To see what the tokenizer had done behind the scenes, let’s have a look at a few texts in a batch.

data = TextClasDataBunch.from_csv(path, 'texts.csv')

data.show_batch()

The texts are truncated at 100 tokens for more readability. We can see that it did more than just split on space and punctuation symbols:

- the “‘s” are grouped together in one token

- the contractions are separated like this: “did”, “n’t”

- content has been cleaned for any HTML symbol and lower cased

- there are several special tokens (all those that begin by xx), to replace unknown tokens (see below) or to introduce different text fields (here we only have one).

Numericalization

Once we have extracted tokens from our texts, we convert to integers by creating a list of all the words used. We only keep the ones that appear at least twice with a maximum vocabulary size of 60,000 (by default) and replace the ones that don’t make the cut by the unknown token UNK.

The correspondance from ids to tokens is stored in the vocab attribute of our datasets, in a dictionary called itos (for int to string).

data.vocab.itos[:10]

And if we look at what a what’s in our datasets, we’ll see the tokenized text as a representation:

data.train_ds[0][0]

But the underlying data is all numbers

data.train_ds[0][0].data[:10]

With the data block API

We can use the data block API with NLP and have a lot more flexibility than what the default factory methods offer. In the previous example for instance, the data was randomly split between train and validation instead of reading the third column of the csv.

With the data block API though, we have to manually call the tokenize and numericalize steps. This allows more flexibility, and if you’re not using the defaults from fastai, the various arguments to pass will appear in the step they’re revelant, so it’ll be more readable.

data = (TextList.from_csv(path, 'texts.csv', cols='text')

.split_from_df(col=2)

.label_from_df(cols=0)

.databunch())

Language model

Note that language models can use a lot of GPU, so you may need to decrease batchsize here.

bs=48

Now let’s grab the full dataset for what follows.

path = untar_data(URLs.IMDB)

path.ls()

(path/'train').ls()

The reviews are in a training and test set following an imagenet structure. The only difference is that there is an unsup folder on top of train and test that contains the unlabelled data.

We’re not going to train a model that classifies the reviews from scratch. Like in computer vision, we’ll use a model pretrained on a bigger dataset (a cleaned subset of wikipedia called wikitext-103). That model has been trained to guess what the next word is, its input being all the previous words. It has a recurrent structure and a hidden state that is updated each time it sees a new word. This hidden state thus contains information about the sentence up to that point.

We are going to use that ‘knowledge’ of the English language to build our classifier, but first, like for computer vision, we need to fine-tune the pretrained model to our particular dataset. Because the English of the reviews left by people on IMDB isn’t the same as the English of wikipedia, we’ll need to adjust the parameters of our model by a little bit. Plus there might be some words that would be extremely common in the reviews dataset but would be barely present in wikipedia, and therefore might not be part of the vocabulary the model was trained on.

This is where the unlabelled data is going to be useful to us, as we can use it to fine-tune our model. Let’s create our data object with the data block API (next line takes a few minutes).

data_lm = (TextList.from_folder(path)

#Inputs: all the text files in path

.filter_by_folder(include=['train', 'test', 'unsup'])

#We may have other temp folders that contain text files so we only keep what's in train and test

.split_by_rand_pct(0.1)

#We randomly split and keep 10% (10,000 reviews) for validation

.label_for_lm()

#We want to do a language model so we label accordingly

.databunch(bs=bs))

data_lm.save('data_lm.pkl')

We have to use a special kind of TextDataBunch for the language model, that ignores the labels (that’s why we put 0 everywhere), will shuffle the texts at each epoch before concatenating them all together (only for training, we don’t shuffle for the validation set) and will send batches that read that text in order with targets that are the next word in the sentence.

The line before being a bit long, we want to load quickly the final ids by using the following cell.

data_lm = load_data(path, 'data_lm.pkl', bs=bs)

data_lm.show_batch()

We can then put this in a learner object very easily with a model loaded with the pretrained weights. They’ll be downloaded the first time you’ll execute the following line and stored in ~/.fastai/models/ (or elsewhere if you specified different paths in your config file).

learn = language_model_learner(data_lm, AWD_LSTM, drop_mult=0.3)

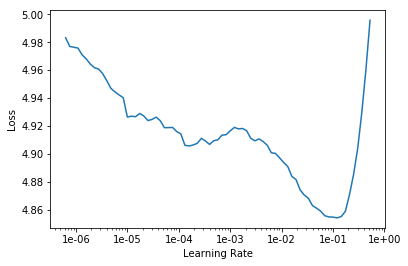

learn.lr_find()

learn.recorder.plot(skip_end=15)

learn.fit_one_cycle(1, 1e-2, moms=(0.8,0.7))